CTG, Mix Shift and Performance Effect

The Tldr:

Contribution to growth (CTG), Mix Shift and Performance Effect are analytical tools for gaining insight into the relationship between overall vs. segment level changes-be it customer, product, marketing channel, region or time segments.

CTG can be broken down to Mix Shift + Performance Effect

Granular CTG adds up to independently calculated aggregate CTG.

Granular Mix Shift or Performance Effect does not however add up to independently calculated aggregate Mix Shift or Performance Effect. This is due to the presence of interaction terms.

Templates and examples for calculating CTG, Mix Shift and Performance Effect are in this spreadsheet. For details on relevant formulas, applications and their derivations, read on below.

In product and business, understanding drivers of growth is crucial for decision making. Concepts that play a significant role in this analysis are contribution to growth (CTG), Mix Shift and Performance Effect.

Contribution to growth helps identify how much individual components contribute to overall growth. Mix Shift digs further into the individual elements to delineate how much of its contribution comes from changes in its own performance vs. changes in its relative size amongst the components. Performance Effect is simply the part of the component’s CTG that was due to its own performance and not due to change in its relative size amongst components - in other words, Peformance Effect = CTG - Mix Shift

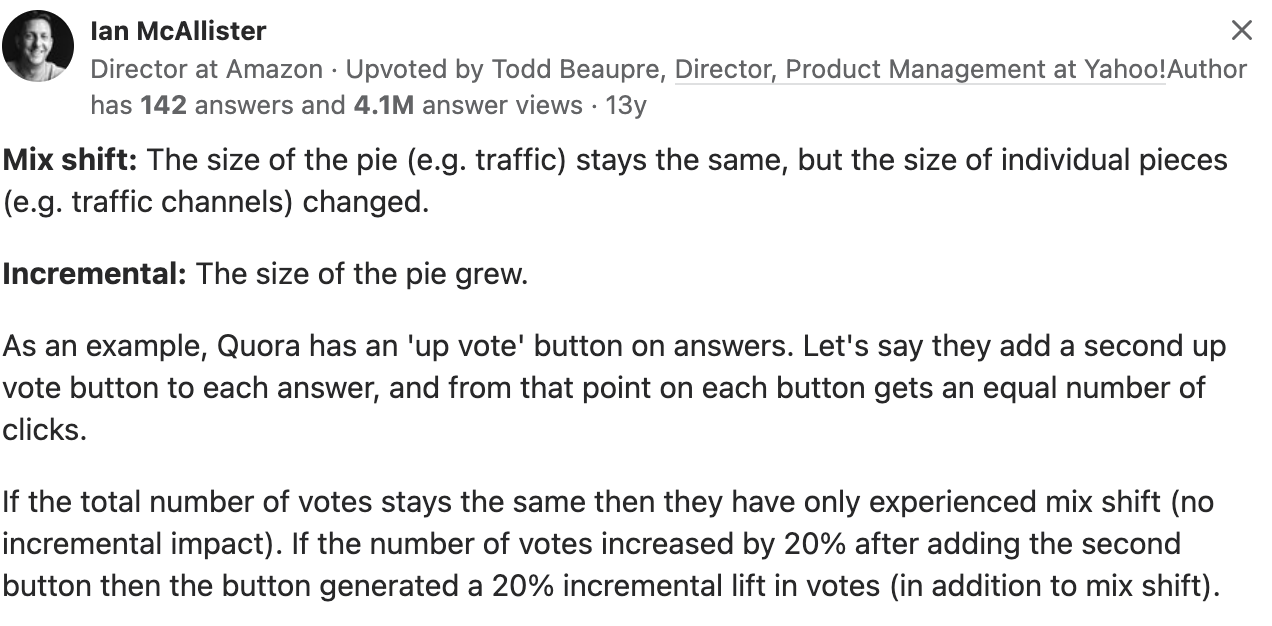

Here’s a great explanation from Quora

And here’s an interview question from Meta, where a Mix Shift lens would be applicable.

To really concretize the above, let’s consider a hypothetical example.

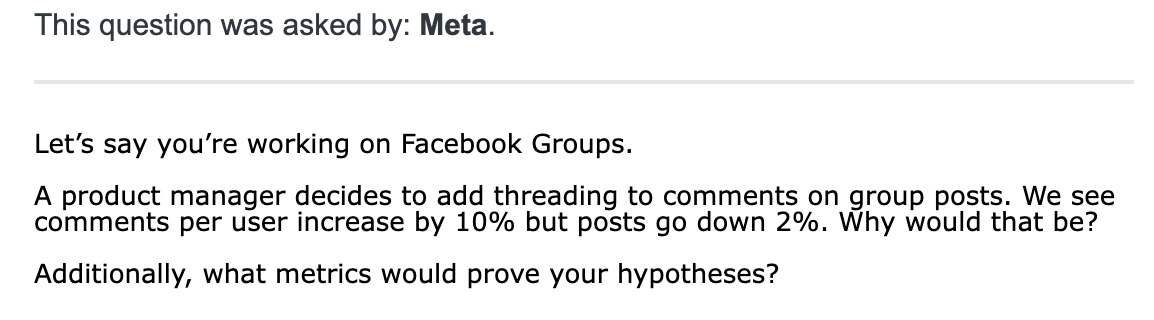

Suppose we work at an ecommerce company and we see that new user Activation i.e. the % of new visitors who have bought something, has dropped by 20 bps between this year and last year.

Note: In this essay year-over-year for percentage values are expressed in absolute difference in the percentages i.e. in basis points.

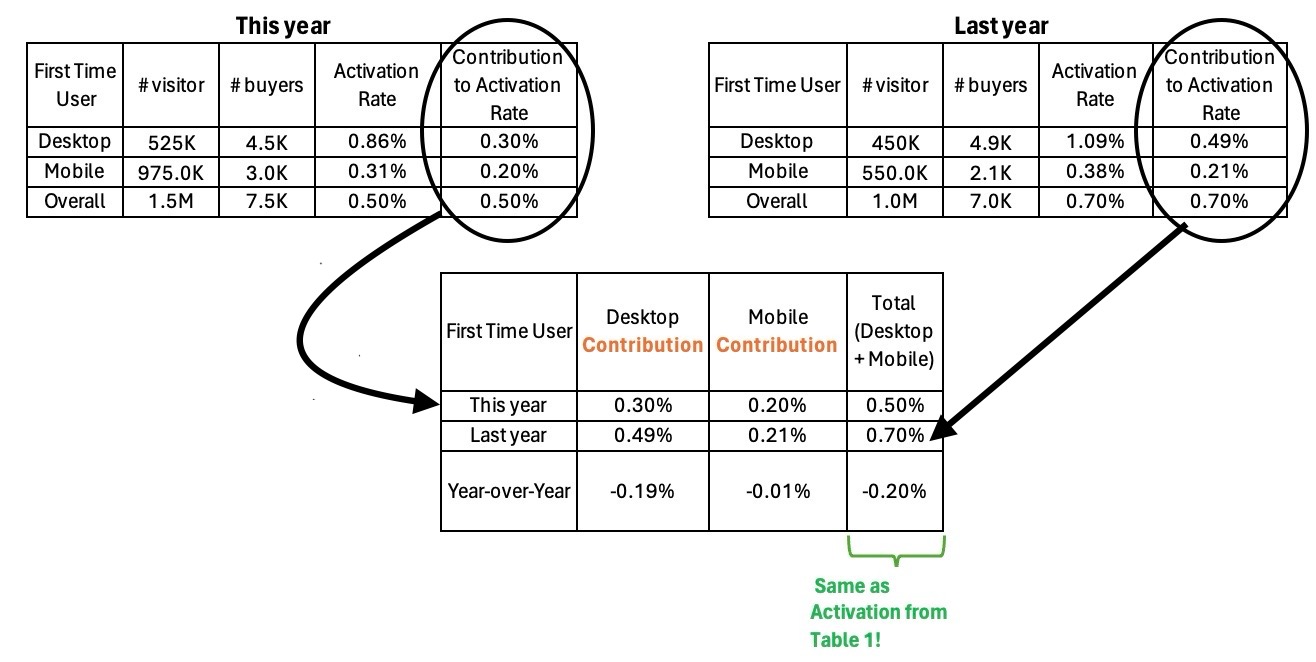

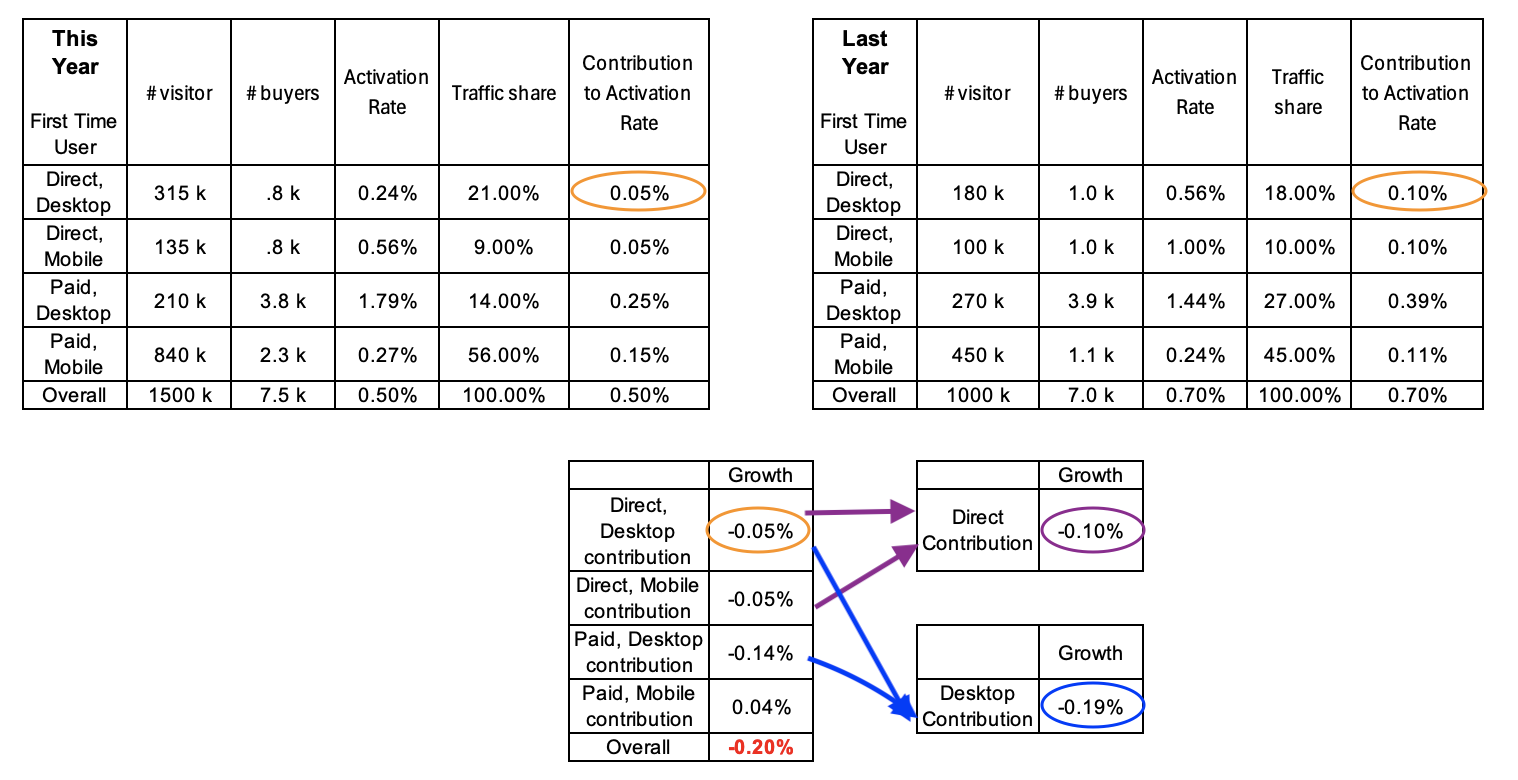

Table 1: Activation this year is 20 bps lower than last year

Users access the business through either the Desktop or Mobile website. We are therefore interested in knowing the contribution of each platform to the 20 bps drop.

Approaching Contribution to Growth:

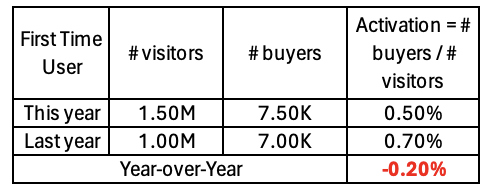

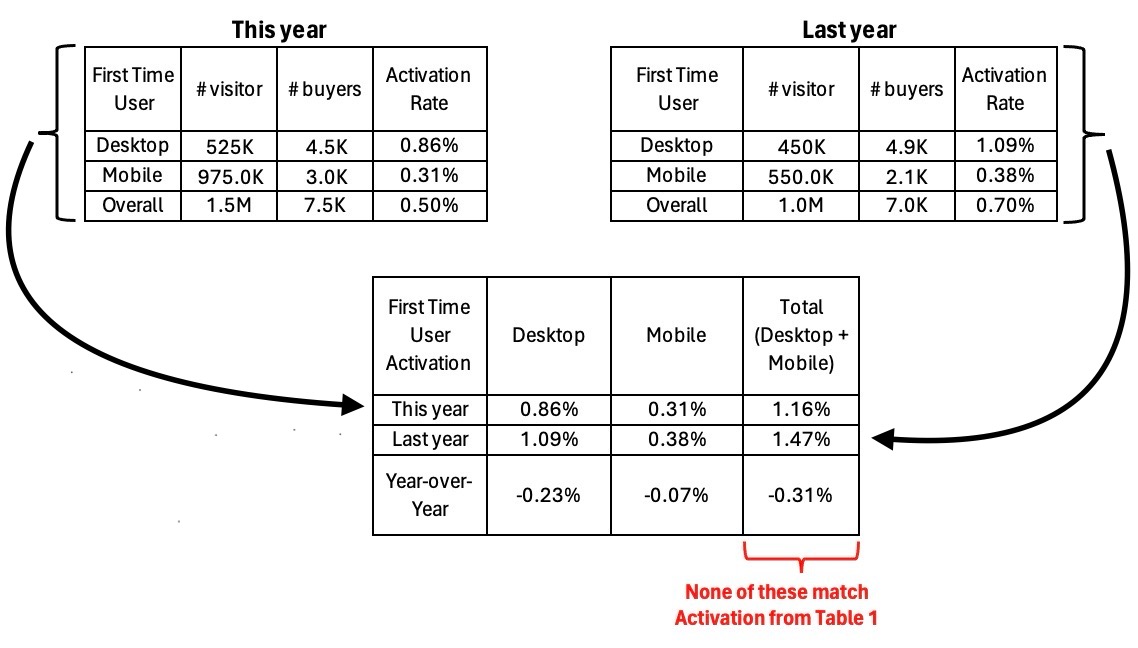

A natural impulse may then be to find the Year-over-Year Activation changes for Desktop and Mobile respectively and add them up. However, as the table below shows, that does not work: the sum of individual Year-over-Year Activation yields a total of -31 bps, which is different from the expected total of -20 bps.

Table 2: Illustrating that Year-over-Year component rate changes is not equal to component contribution to overall growth

Instead, what we need to do is:

- Calculate Desktop and Mobile’s contribution to activation for each year

- Subtract each platform’s contribution to last year’s activation from its contribution to this year’s activation.

Table 3: Illustrating that Year-over-Year component contribution to overall rate changes is equal to component contribution to overall growth

So in contrast to the incorrect approach where the actual activation was used, the right calculation requires using the within year contribution to activation. Using this calculation we find that in our example, 19 of the 20 bps drop is attributable to Desktop.

Now the question becomes - how do we find the within year contribution to activation? There are a few methods for doing so, two of which are illustrated below.

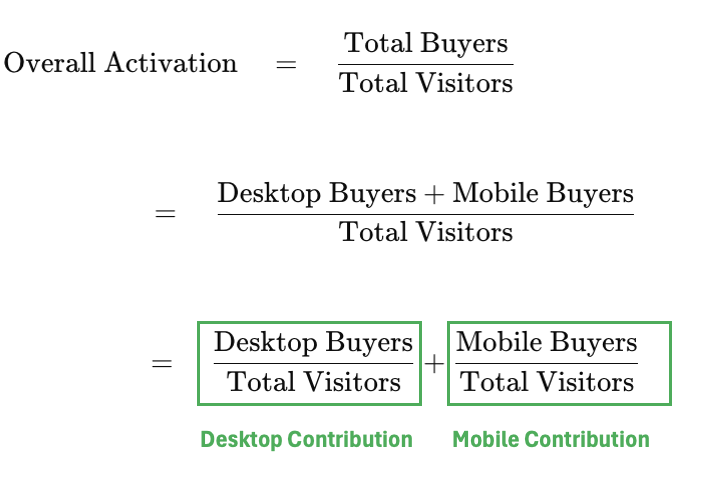

Contribution to Rate: Method 1

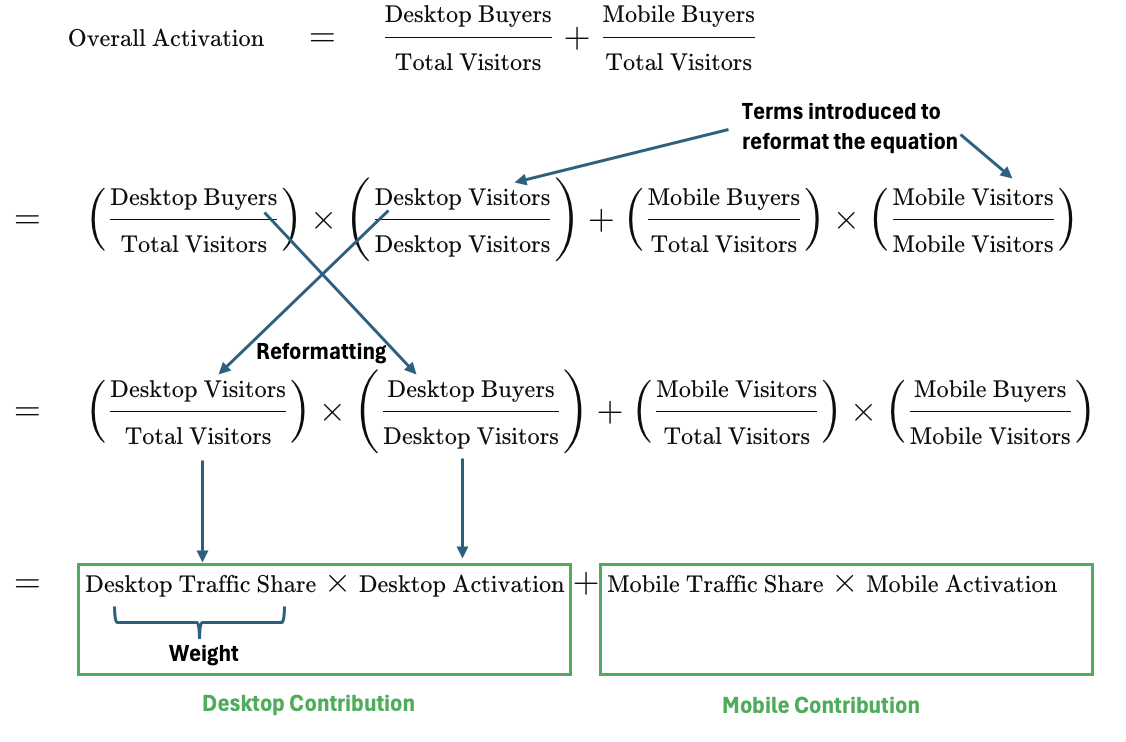

This easiest way to grasp this method is by following the below equation:

Using this year’s numbers for illustration, we get:

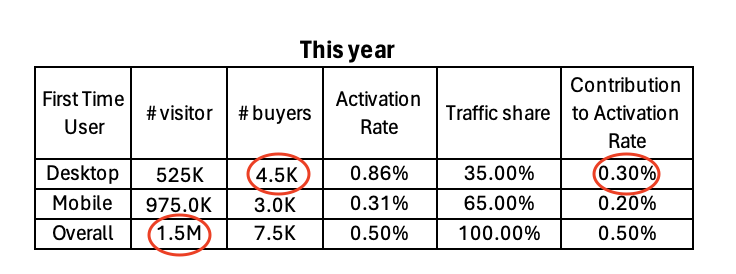

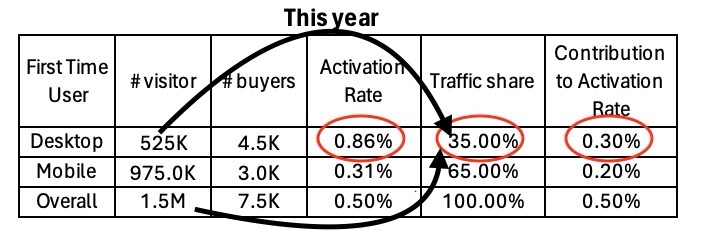

A tabular representation of the above, with the circles indicating the inputs and output of Desktop contribution to rate calculation:

Table 4: # desktop buyers / # overall visitors = desktop contribution to overall rate

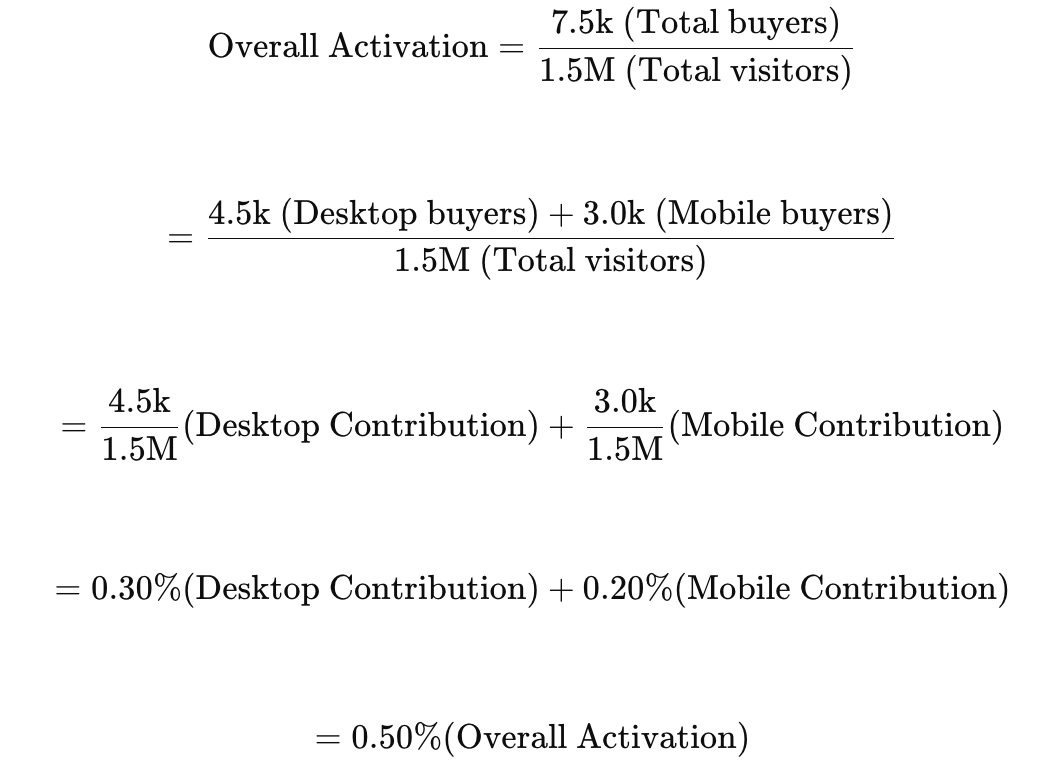

Contribution to Rate: Method 2

The second method is actually an extension of the first method. This might beg the question, why bother with a second method at all? The reason is that this method serves as the basis for mix shift calculation-to be illustrated later.

To understand the second method, we start with the formula for the first method and introduce a new variable to reformat the equation. This will become clear through the derivation below:

This second method shows us that the overall activation rate can be expressed as the weighted sum of each platform’s activation rate. The weight of each platform is its traffic share or in other words how often that platform is accessed compared to other platforms.

A tabular representation of the above, where the arrows show the inputs to the Desktop traffic share (i.e. weight) calculation; and the circles show the inputs to the Contribution to Activation Rate calculation is shared below.

Table 5: Desktop contribution to overall rate = Desktop rate * Desktop traffic share; where Desktop traffic share = Desktop visitors / Overall visitors

Contribution to Growth Formula

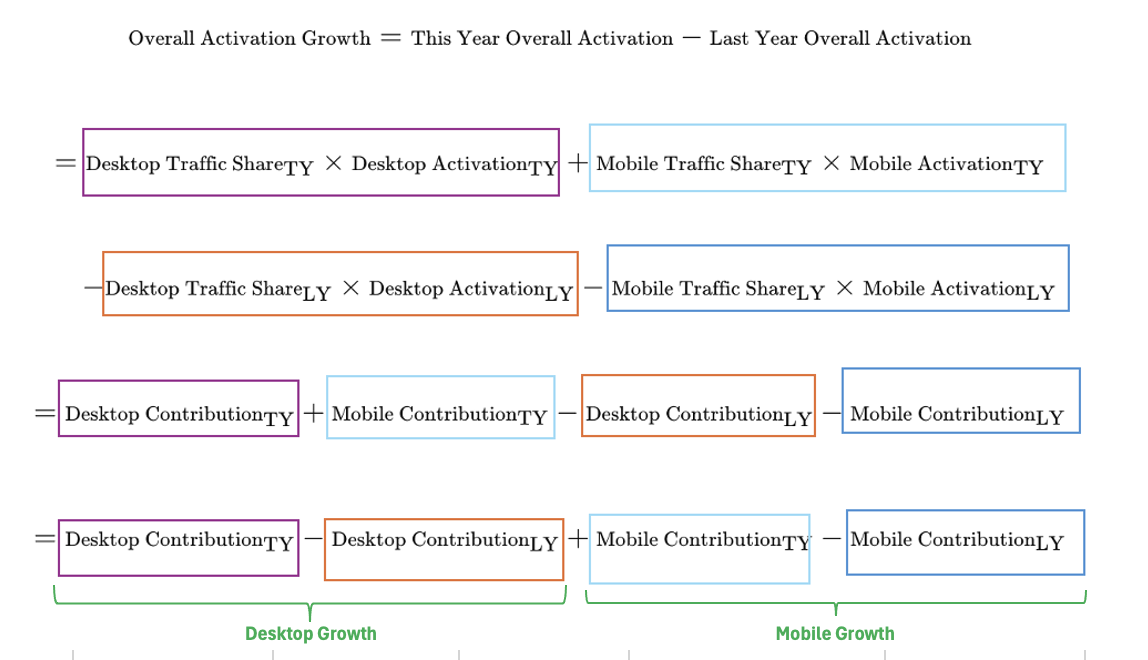

We have gone through the steps for calculating Contribution to Growth before, but let us now succinctly illustrate it with a formula as well. Note that components of the equation are color coded to make them easier to track as they are reformatted and repositioned.

Since the tabular view for this calculation has already been shared at the beginning, we will move on to looking at what the Mix Shift analysis entails.

Mix shift

Before diving into the Mix shift formula, let us quickly recap what we have examined so far, as that will set the context for why looking into Mix Shift is interesting.

We have seen between this year and last year there has been a 20 bps drop in overall activation rate. We have also seen that the entirety of this drop is attributable to the Desktop platform.

In the section Contribution to Rate: Method 2, we have seen that: Component Contribution to Overall Rate = Component Traffic Share x Component Rate. And per Contribution to Growth Formula section, this implies that Component Contribution to Growth can be driven by Component Traffic Share (Mix) changes and/or Component Rate (Performance) changes.

Given the above, the question now becomes, has Desktop’s contribution to the overall drop been due to Desktop Activation Rate getting worse? Or has it been due to more visitors accessing Mobile this year relative to Desktop? It may also be due to both-in which case, we would want to know how much Performance vs. Traffic change contributed to Desktop’s contribution change.

The above breakout would be useful to know, as that would help us decide where and how much to invest in the solution for each problem.

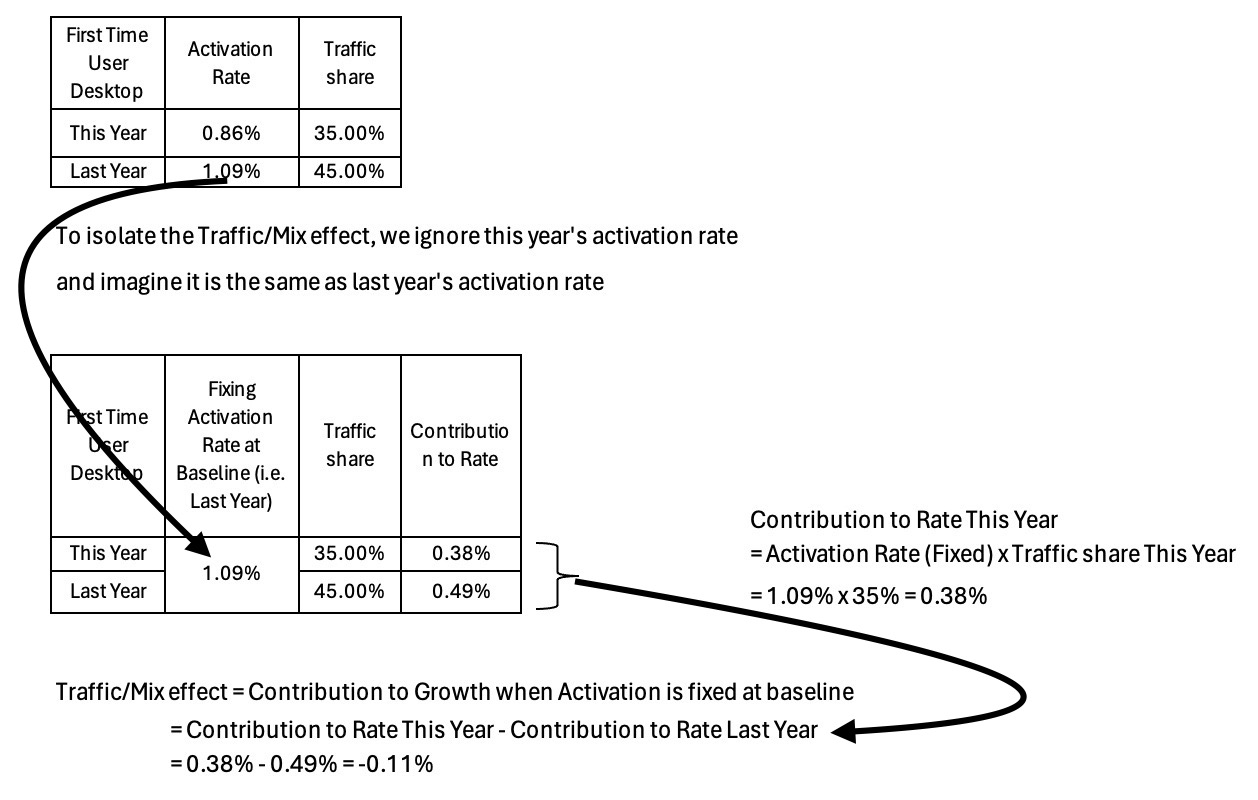

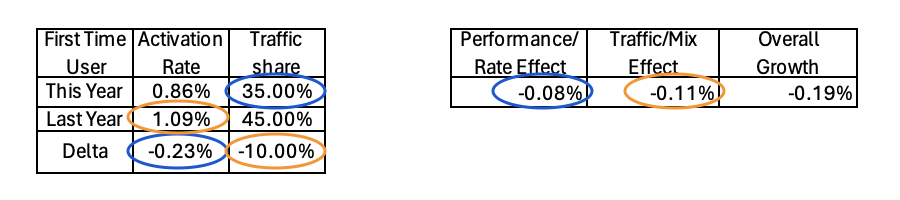

Now the Mix Shift formula looks to isolate how much of the Contribution to Growth is due to changes in Traffic Share or Mix. Quite simply it considers if the component performance remained constant at baseline levels (at a prior year for instance) but experienced a Traffic Share change, how would its Contribution to Growth change. The tabular representation for this, using the Desktop platform as an example is shown below.

Table 6: Illustrating the Traffic/Mix effect using Desktop platform’s numbers

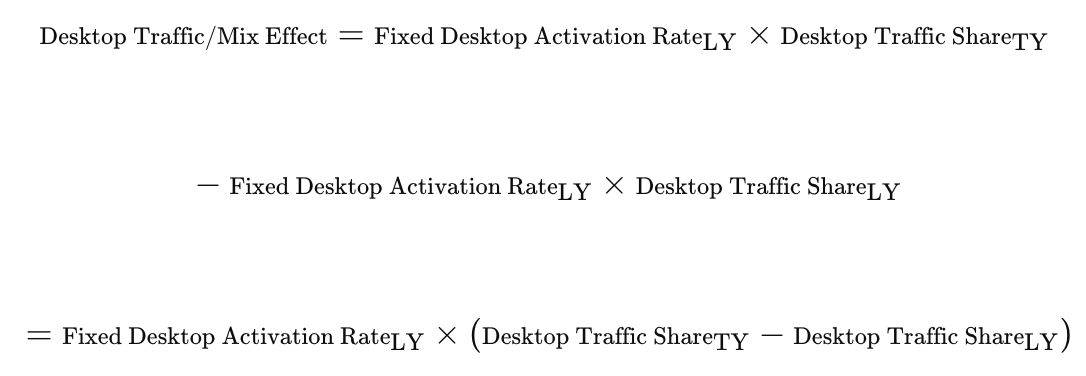

The formula that corresponds to the above depiction is:

Having looked at the Traffic/Mix effect, we need to acknowledge that it may not account entirely for the Component Contribution to Overall Growth.

To elaborate – in Table 3, we have seen that Desktop Contribution to Growth was -0.20 bps, while in Table 6 we have seen that Traffic/Mix effect accounts for -0.12 bps. The -0.08 bps of difference between Desktop Contribution to Growth and its Traffic/Mix effect is due to Component Rate/Performance changes i.e. Desktop Activation Rate changes.

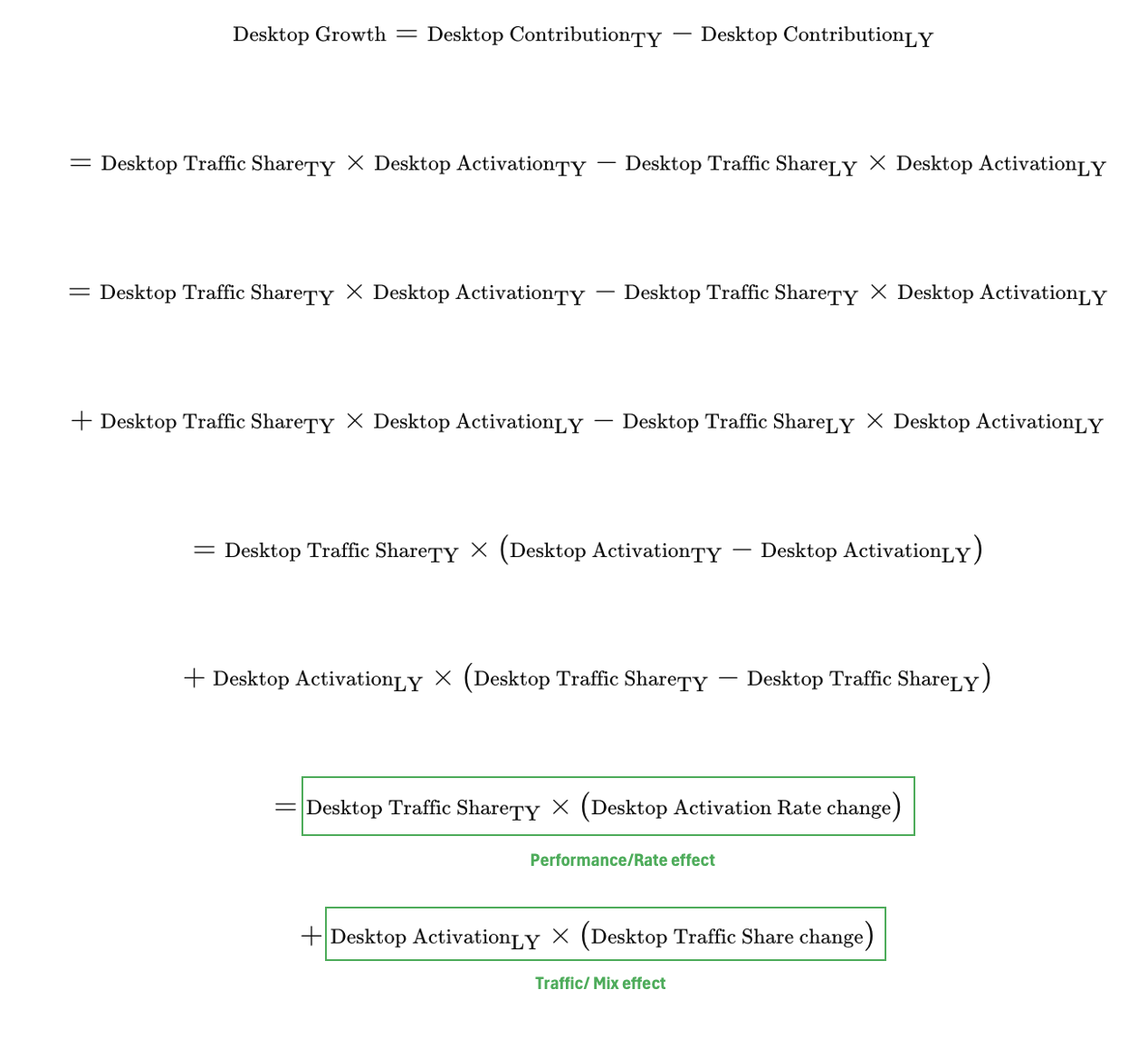

The breakout of the Component Contribution to Growth formula into Performance/Rate Effect and Traffic/Mix Effect is derived below.

Following is a tabular representation of the above formula. The orange circles denote the input and output to Traffic/Mix effect, while the blue circles denote the input and output to Performance/Rate effect:

Table 7: An example showing the rate effect and mix effect, the sum of which equals the component’s contribution to overall growth

CTG and Mix Shift across multiple dimensions:

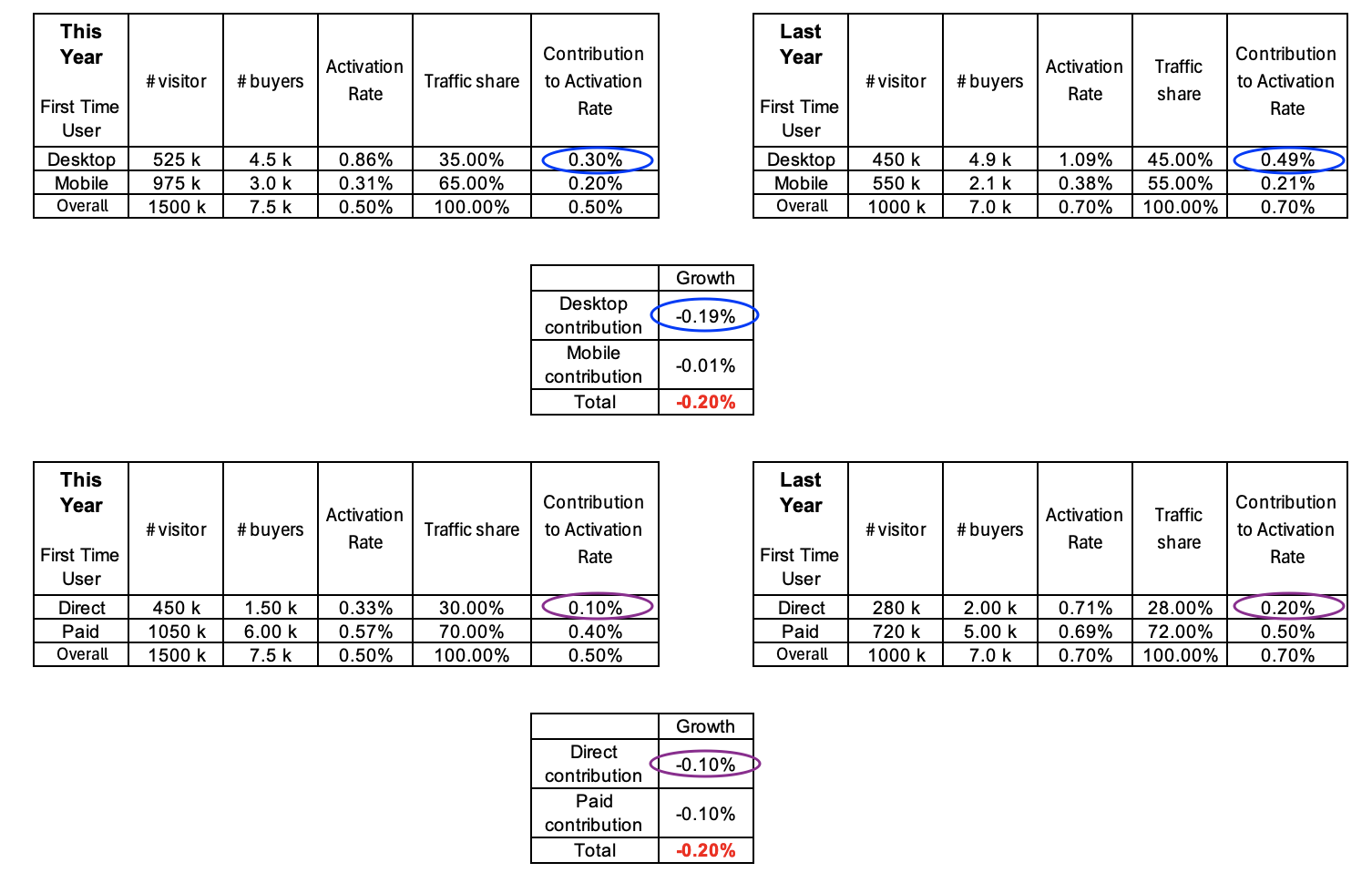

So far, we have examined CTG and Mix Shift using a single dimension: Device Type. Now, let’s explore how these calculations might change when we add another dimension, such as Traffic Type (Direct vs. Paid).

The tables below illustrate that the approach to CTG calculations remains the same for any additional dimension. For instance, the Direct Contribution calculation, indicated by the purple circles, follows the same pattern as the Desktop Contribution, indicated by the blue circles. Of course, the CTG breakdown across each new dimension is different as can also be seen below.

Table 8: An example showing that the total CTG across segments of different dimensions remains consistent

Even the intersection of the two dimensions, as shown in the table below, follows the same CTG calculation pattern, indicated by the orange circles. Moreover, the sum of the granular CTG adds up to the higher-level CTG, as indicated by the arrows.

Table 9: An example showing that the rollup of granular CTG is the same as the independently calculated aggregate CTG from Table 8

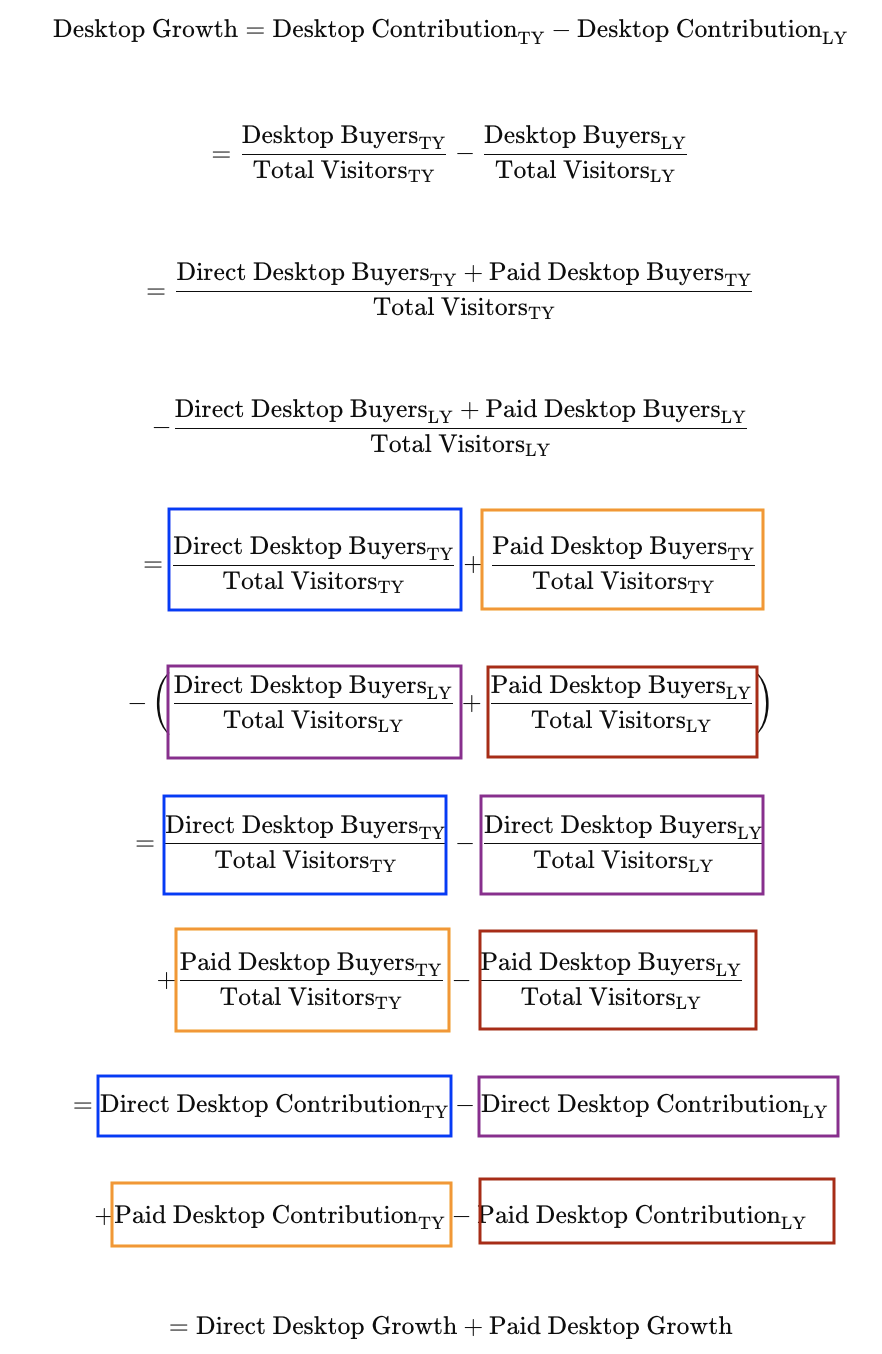

That Desktop Growth can be broken down into Direct, Desktop Growth and Paid, Desktop Growth is shown algebraically below. The colored boxes around terms are to help track them as they are moved and reformatted.

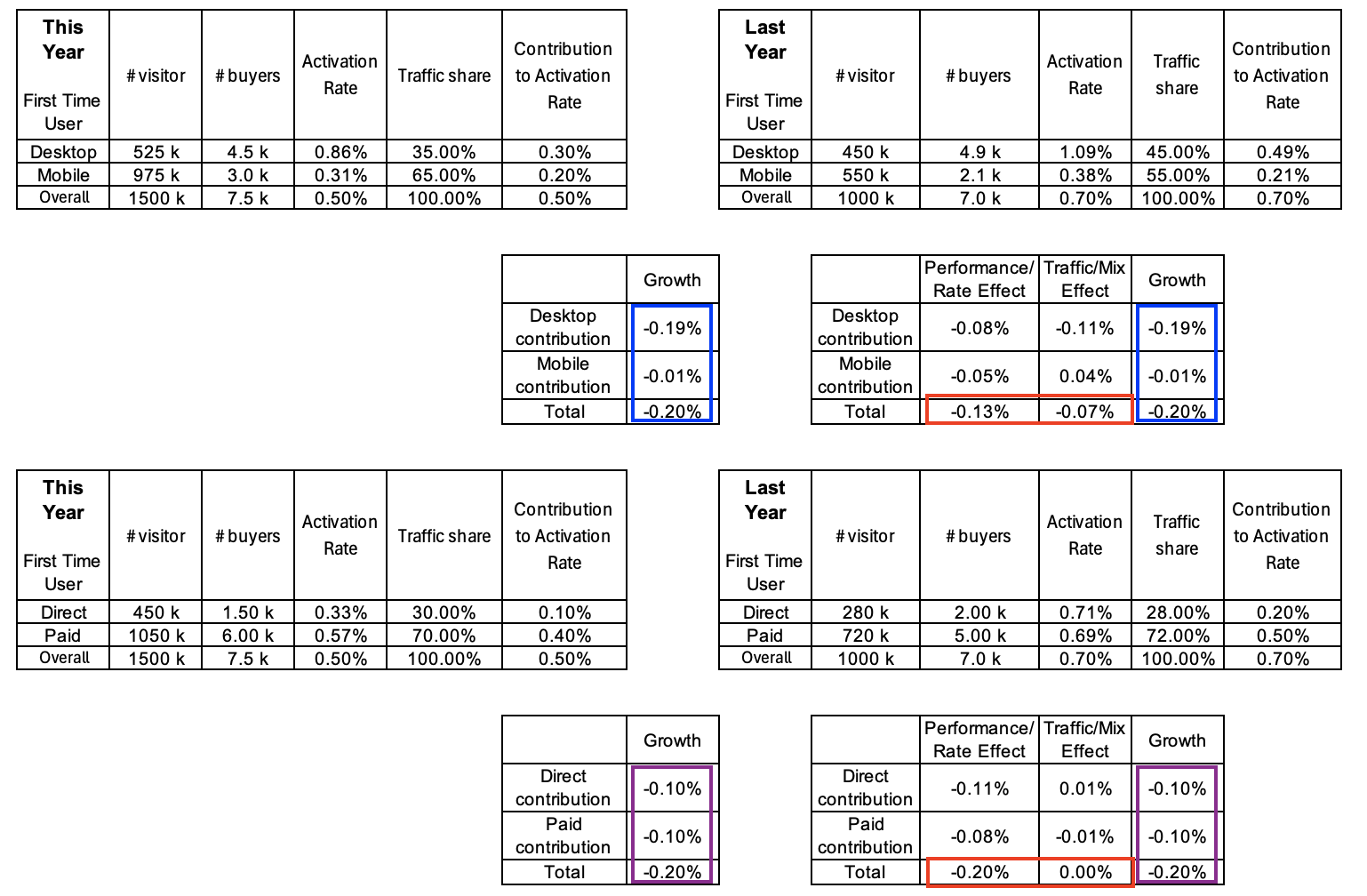

We now turn our attention to the Performance Effect and Mix Effect calculations for additional dimensions. The blue and purple boxes in the tables below show that CTG = Performance Effect + Mix Effect for each dimension, as expected. However as shown by the red boxes, the Performance Effect and Mix Effect calculated across different dimensions do not match against each other.

In other words, while we can comment on overall growth changing by -20 bps and we can see the split of this 20 bps of change across the different dimensions, we cannot however comment on how much of the change in growth was due to rate effect or mix effect independent of dimensions. The total rate effect and mix effect is a function of the dimension under consideration.

Table 10: Illustration that while CTG calculated by different approaches remains consistent, total Rate Effect and Mix Effect depends on the dimension for which it is calculated

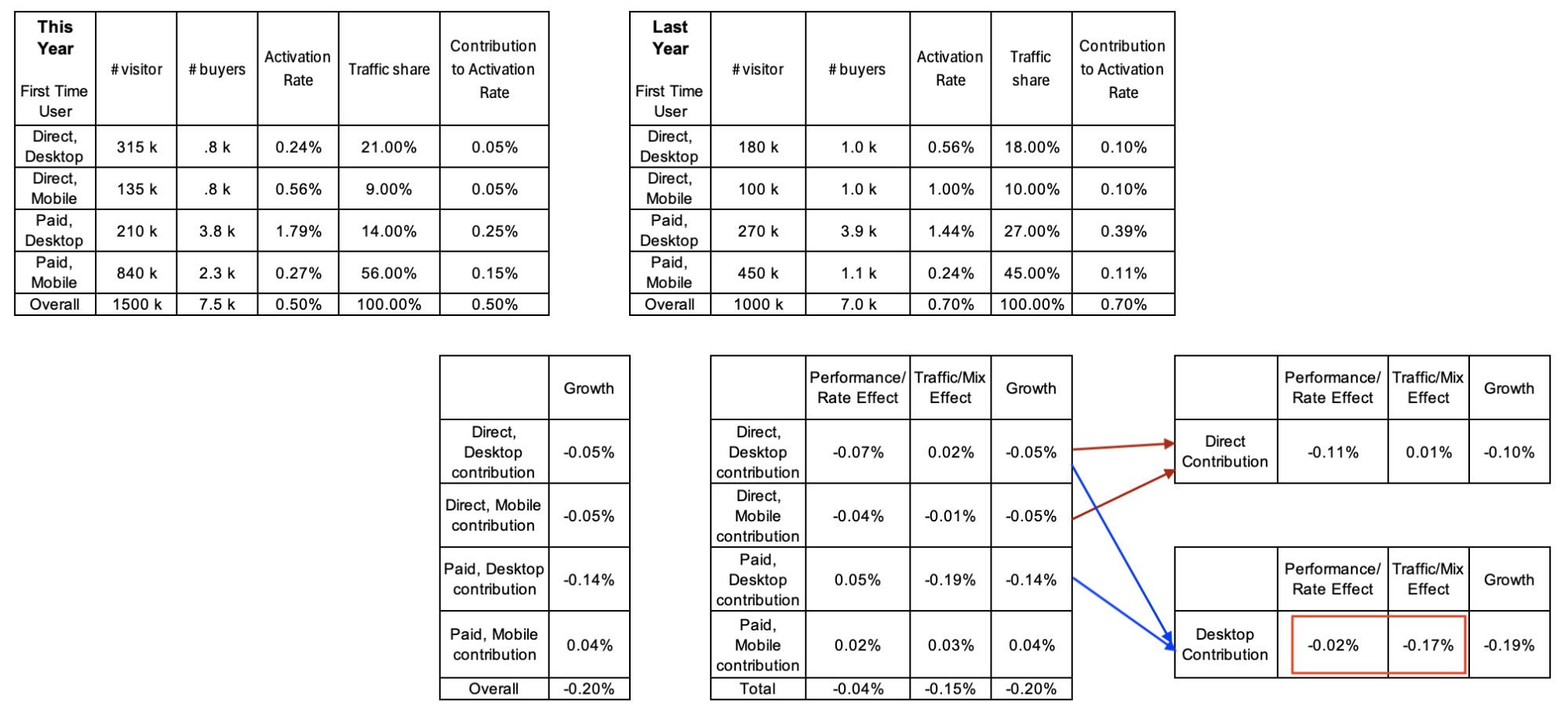

Moreover, as can be seen from the tables below, the addition of the granular Rate Effect and Mix Effect does not necessarily roll up to independently calculated aggregate Rate Effect and Mix Effect for a dimension. This can be seen as in the case of the red box highlighting the Desktop Performance Effect and Mix Effect below.

Table 11: Illustration that the granular Rate Effect or Mix Effect may not roll up to the independently calculated aggregate Rate Effect or Mix Effect

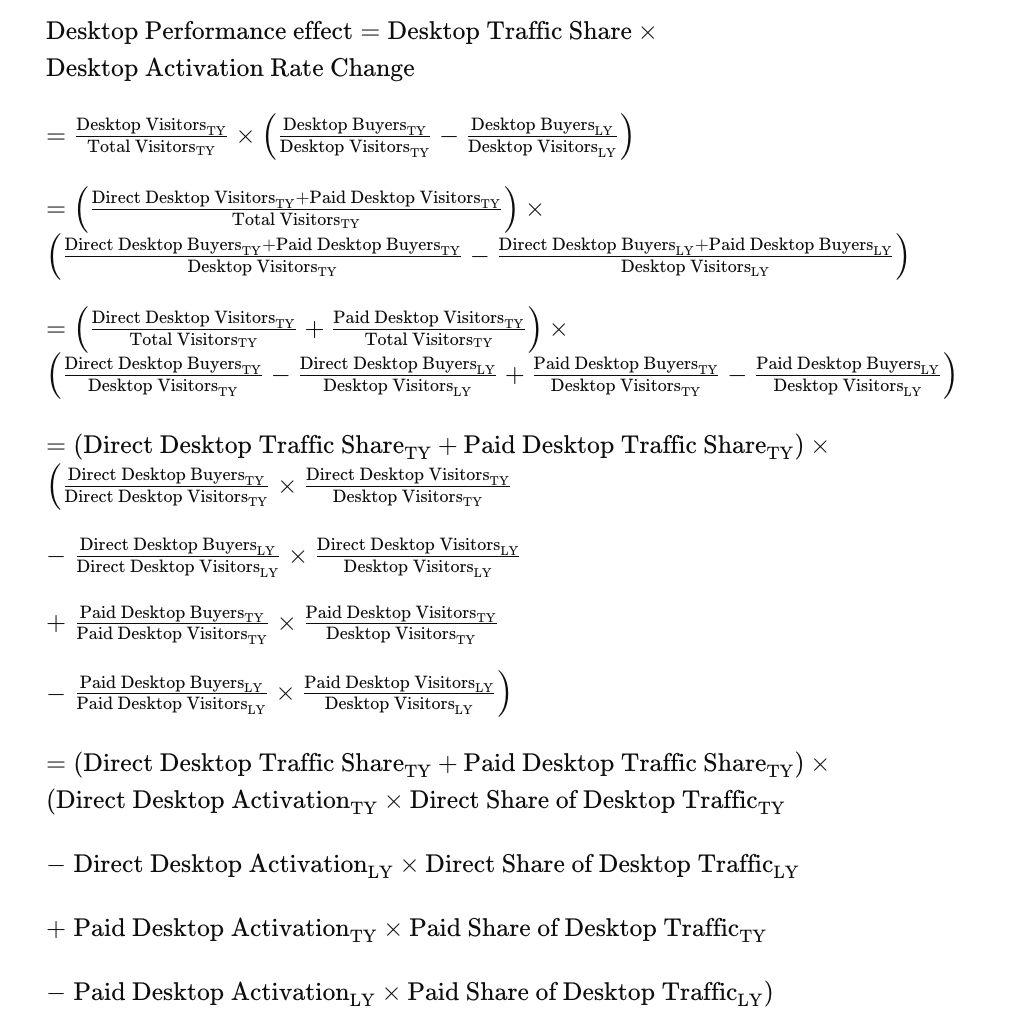

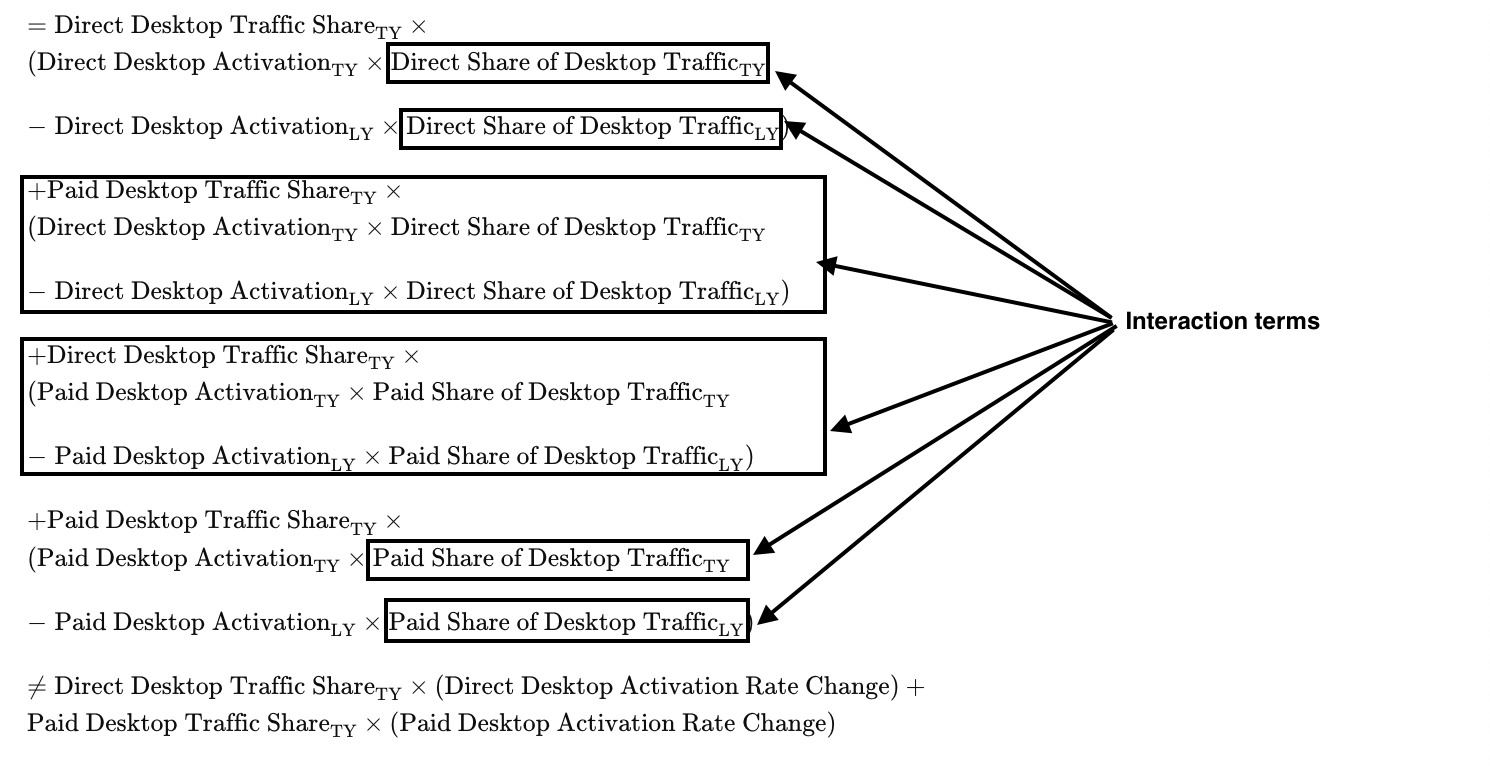

In fact it can be shown algebraically the Desktop Performance effect does not break down into the sum of Direct Desktop Performance effect and Paid Desktop Performance effect. This is due to the presence of interaction terms that is highlighted in the derivation below.

A similar exercise to the above can be used to also illustrate that Desktop Mix effect does not break down into the sum of Direct Desktop Mix effect and Paid Desktop Mix effect, again due to the presence of interaction terms.

However it must be noted that the sum of Desktop Performance effect and Desktop Mix effect does indeed break down to Direct Desktop Performance effect, Paid Desktop Performance effect, Direct Desktop Mix effect and Paid Desktop Mix effect i.e. consistent with Desktop CTG breaking down into Direct Desktop CTG and Paid Desktop CTG.

All this to say, both levels of Performance effect and Mix effect are correct in their own context, even though the granular view does not “add up” to the aggregate view. In fact any expectation of things “adding up” would be incorrect. The right way to think of the aggregate Performance Effect is that it is a function of the granular Performance Effect and interaction terms. The same relationship also holds between aggregate and granular Mix Effects.

Related reads: