Does reducing fees increase revenue: Testing approach, inferring results, next steps if test fails [5/7]

Posts in the series: Intro, 1/7: Context and TAM, 2/7: A conceptual model, 3/7: Externalities and breaking even, 4/7: Dynamics over time, 5/7: Testing approach, inferring results, next steps if test fails , 6/7: Metrics , 7/7: Takeaway, Google Sheets with data

Section 6: What should be our testing approach?

Generally A/B tests or perhaps A/B/C/../n tests are carried out to validate ideas in our marketplace. However in case of an allotment change, a simple A/B test or A/B/C/../n test may be subject to network interference bias

Basically what it means in this context is that if we had a test group with 30 allotments and a control group with 20 allotments, then the increase in listings from the test group would not just impact GMV for the test group but also that of the control group. In short, the GMV for the test and control groups are not independent.

One way this may happen is that the incremental listings from the test group creates price competition that forces ASP down and therefore GMV down for both test and control groups! Or sellers in the control group may react to the additional inventory on the site by increasing their listings, changing their marketing strategy such as by using “Promoted listings” feature. And these are impacts on the control group that may happen within the first month of the allotment test; if the test group triggers a flywheel effect which results in loss or gain of buyers or sellers, that would also impact both test and control groups.

There are some standard ways to remove interference such as splitting the test by region or time. However these are not applicable in our monthly allotment test where buyers and sellers transact across the US i.e. they do not limit themselves to local markets.

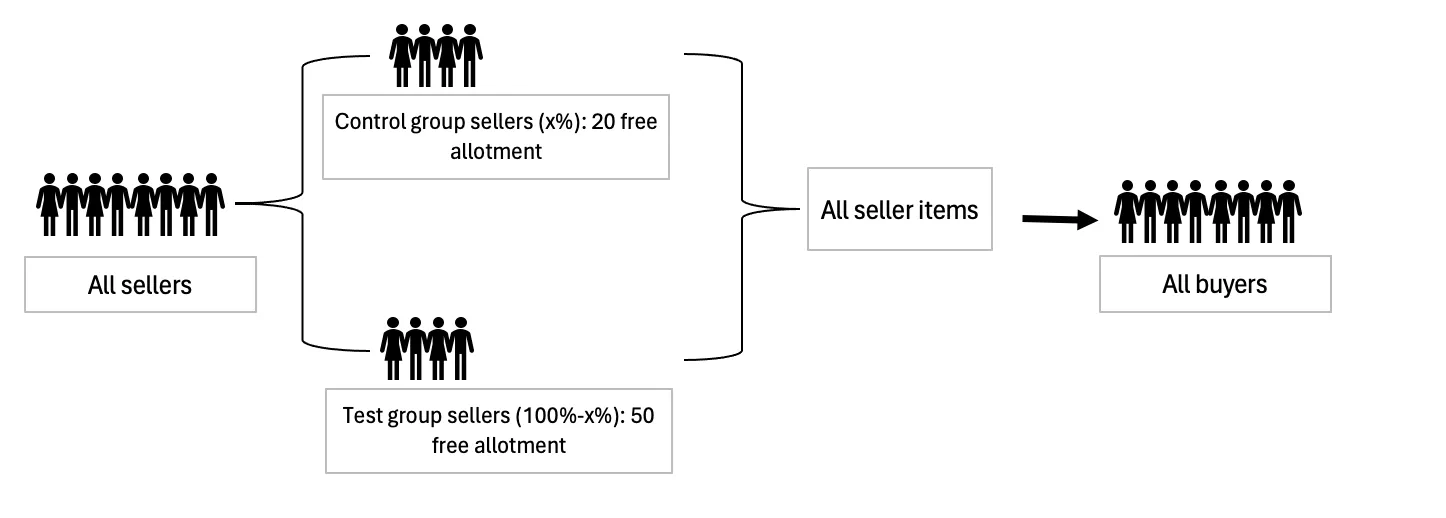

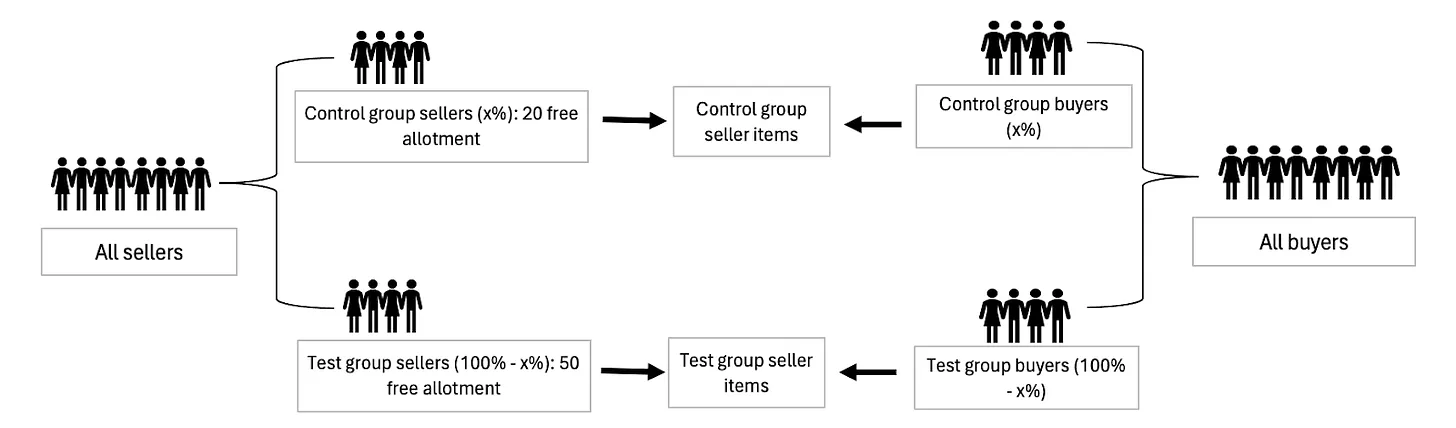

One way to remove interference that may actually be applicable in our context is: splitting buyers to map them into the seller test and control groups, meaning some buyers will only be exposed to the test group while the remaining buyers will be exposed to the control group. The distinction from regular A/B tests is illustrated in the diagrams below.

Figure 2: Traditional A/B testing approach where sellers are split into test and control. In the case of the allotment test, such a split is likely to create interference bias in GMV measurements

Figure 3: In this approach, buyers are split in proportion to and then mapped to seller groups in order to remove interference bias

This buyer splitting approach could allow multiple allotments to be tested at the same time, however there are some challenges. For instance, a buyer meant for the control group may land on an item from a seller in the test group through external channels such as Google search or through the seller’s external marketing such as on Facebook. This would contaminate the test results. Moreover, the buyer experience on the site through search, browse and product recommendations may be quite different when they have the full site inventory at their disposal versus a subset. In fact, this may be particularly true when buyers from some groups miss out on long tail inventory from sellers in other groups. So in a situation where the sum may be greater than the parts, there may be questions around the external validity in the form of generalizability of this test.

Finally, a method of testing that would ensure there is no interference is by doing an Event Study. In such a validation approach, we can test only one allotment at a time and compare against an expected baseline that is an estimate of how the control group would have trended. This would mean for instance that we run a 50 allotment test sitewide for 3 months and compare it with a time series forecast of how a 20 allotment group would have performed at the same time, using actual historical data for 20 allotments. The expected baseline trend would have to adjust for seasonality and any other product or business changes that may impact inventory or GMV levels. So for instance, if there is an improved checkout flow that enables more buyer conversion-the GMV lift from this launch (that we should very likely know from its AB test) needs to be incorporated into our baseline.

Some downsides of this method are that: 1) the measurement accuracy of the incremental values is extremely dependent on the forecast accuracy of the baseline and 2) it may not be possible to state the statistical significance of measurements after doing ad hoc adjustments like removing contributions of various launches during the period of the Event Study

Given all the options, the approach that might have the least downsides might be the buyer split approach, but testing only one variant with a 95% to 5% test vs. control split. Such a split would ensure that the test group buyers have as close to the actual experience as possible of seeing the entirety of the inventory. The test group buyers would also have a low probability of seeing control sellers’ inventory just because the size of the control group is so small. While a downside still exists of control group buyers’ seeing test sellers’ inventory, even after removing this effect the baseline offered by this control group will still be more reliable than a forecast based baseline in an Event Study. So this approach would both minimize interference and have a reliable baseline for measurement and understanding the statistical significance of the measurement.

Section 7: Can we infer incremental revenue at one allotment from other allotments?

Being able to test only one allotment every 3 months massively limits us in the number of allotments we are able to test. It would be efficient, if instead of testing all the allotments we are interested in, we could test some allotments and interpolate or infer the incremental revenue (as that is our primary success metric) of the allotments in between.

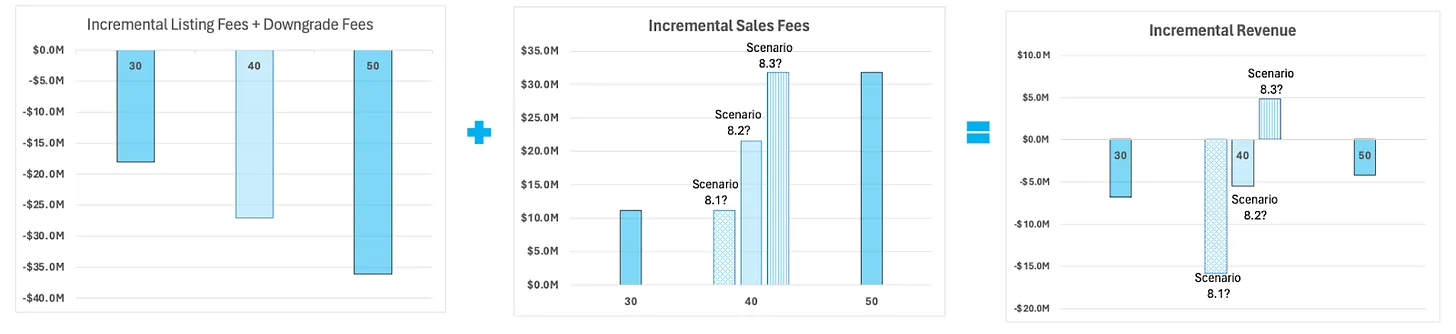

To understand what could be inferred for intermediate allotments from adjacent allotments, let us once again use a conceptual model. We return to Scenario 3.1 with aggressive store downgrades. Let us say we have tested allotments 30 and 50 and would like to find out the bounds of the incremental revenue at allotment 40. What might that look like?

The example below illustrates that the inferred bounds of incremental revenue for the intermediate allotment may span both negative and positive values and therefore result in an ambiguous conclusion. If we were able to definitively establish that the intermediate allotment would yield negative incremental revenue then we could have confidently rejected that allotment as failing our success criteria; the indefinite state of the inferred information means we lack actionable insights.

Chart 17: A conceptual example to illustrate the inferred bounds of incremental revenue for intermediate allotment 40

To elaborate on how we got the above chart, we first of all need to note that incremental revenue is the sum of incremental listing fees, forgone store downgrade fees and incremental sales fees. The dark blue bars indicate data obtained from testing and the lighter bars indicate estimated data.

Now we have already modeled the incremental listing fees and forgone store downgrade fees previously in Sections 2 and 3 respectively – our model indicates that the sum of incremental listing fees and forgone store downgrade fees for 40 allotments will be somewhere _in between _30 and 50 allotments.

This leaves us with predicting the incremental sales fees for 40 allotments. Can we say that just as in the case of incremental listing fees and store downgrade fees, the incremental sales fees at 40 allotment will fall somewhere in the middle of the sales fees of 30 and 50 allotment?

We do not believe that to be the case. Incremental listing fees and forgone store downgrade fees are a function of seller (lister) behavior and therefore change proportionally as sellers scale with allotment changes. Sales fees on the other hand are a function of both the number of available listings and conversion i.e. how relevant those listings are for the buyers. In contrast to the proportional changes in listing fees and store downgrades with allotment changes, changes in conversion rate may be more volatile.

For instance in Scenario 8.1 in the charts above, we assume none of the incremental listings at 40 allotments (with the respect to 30 allotments) convert and therefore sales fees at 40 allotments is the same as that in 30 allotments.

On the other hand in Scenario 8.3, we assume the incremental listings at 40 allotments (compared to 30 allotment) convert at a very high rate while none of the incremental listings at 50 allotment (compared to 40 allotments) convert, resulting the sales fees being the same at 40 allotments and 50 allotments.

In short, the point of these two scenarios which form that upper bound and lower bound of sales and revenue at 40 allotment is to say that even if we know the number of sales at 30 allotments and 50 allotments, we cannot know whether the specific sold items at 50 would have been fully, partially or if at all been available and therefore sold at 40 allotments.

To be clear, there may be instances where we might be able to infer actionable information about an intermediate allotment from adjacent allotments, but it really depends on the data we see at the adjacent allotments.

Also, if the listings curve is indeed logarithmic then if the intermediate allotment we are trying to infer is in the plateau segment of the listings curve, then the bounds for the corresponding incremental revenue will be narrow and therefore may provide us with actionable information.

Moreover, another simple predictive heuristic we may have is that assuming our listings curve is logarithmic, if we do not observe sufficient sold items to generate positive incremental revenue at lower allotments, the likelihood of getting enough sold items to generate positive incremental revenue at higher allotments is low because there may not be enough additional new listings available that may in turn get sold.

In general however, an inference based approach cannot be considered as reliable especially for lower allotment levels.

Section 8: What comes next, if the test fails?

The allotment change test would be considered a failure if it does not end up yielding positive incremental revenue. In this case, we may decide to test another allotment.

An important question would be whether we should test a higher or lower allotment. Per Section 7, we know that we cannot infer the expected conversion or revenue for other allotments from the data at a given allotment. However if we are able to tell if seller behavior is closer to Scenario 3.1 or 3.2 i.e. whether they are conservative or relaxed with their listings budget, then referring to Chart 12 in Section 4 we may be able to understand the direction of the next allotment to select.

Basically should we deem sellers to be conservative with their budget, then given Chart 12 in Section 4, we may want to move up to a higher allotment where there is lower ASP and conversion requirement to breakeven, in the next iteration.

On the other hand if sellers do not seem as conservative with their budget then again per Chart 12 we may want to move to a lower allotment level.

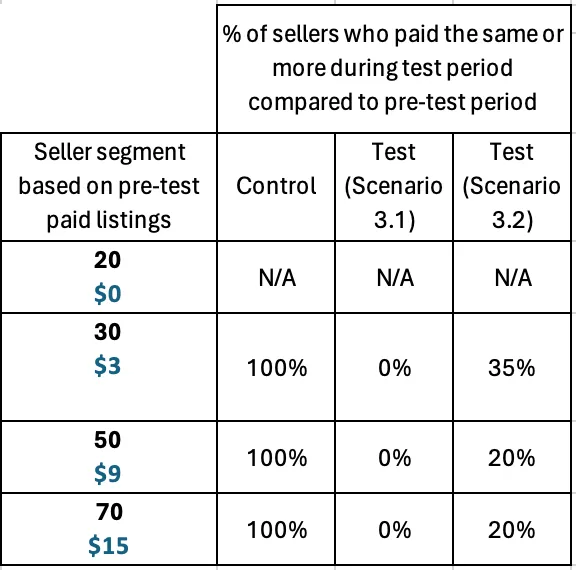

In order to understand whether sellers are being conservative or not, we first create tables similar to Table 3 from Section 2 for both test and control groups. Note that in these tables, in order to compare like sellers, we segment them based on their paid listing behavior in the pre test period. This segmentation is crucial because without it, we would only know how much a seller paid but not whether they paid less or more.

From this first set of tables we then find the percentage of test sellers who are paying the same or more during the test period in comparison to the corresponding control group sellers.

An illustrative example of the result is in the table below.

Table 12: Percentage of sellers who paid the same or more during the test period compared to the pre-test period

The Control column in the above table indicates that all the sellers in the test period who did not experience an allotment change, paid the same or more in listings fees as they did before the test.

In contrast none of the Test (Scenario 3.1) sellers paid the same or more in listing fees compared to the pre test period. This means all the Test (Scenario 3.1) sellers were conservative with their listings budget.

However in Test (Scenario 3.2) some sellers paid the same or more in listing fees compared to the pre test period.

If we observe Test (Scenario 3.1), per Chart 12, testing a lower allotment would mean there would be high conversion and ASP pressure to breakeven. Therefore we may want to test a higher allotment where the required ASP and conversion to breakeven may be more attainable. However the reverse applies to Test (Scenario 3.2).

Posts in the series: Intro, 1/7: Context and TAM, 2/7: A conceptual model, 3/7: Externalities and breaking even, 4/7: Dynamics over time, 5/7: Testing approach, inferring results, next steps if test fails , 6/7: Metrics , 7/7: Takeaway, Google Sheets with data